Bumper Sticker Economics: Can We Balance the Budget?

In Part 5 of our series, we start with the aphorism that the first step to changing is to admit there is a problem. We previously looked at federal revenues and expenditures. What is the result of the recent federal budget deficits?

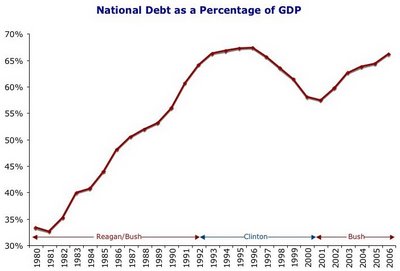

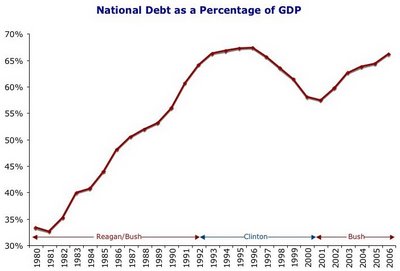

Deficit spending is sending the national debt, as a percentage of GDP, back to the heights (or depths) of the Reagan/Bush era. And with no end in sight to deficit spending, the national debt will continue to grow.

Deficit spending is sending the national debt, as a percentage of GDP, back to the heights (or depths) of the Reagan/Bush era. And with no end in sight to deficit spending, the national debt will continue to grow.

As I said, changing course requires an admission that there is a problem. Instead we hear various expressions of denial.

The first is to maintain the fiction that tax cuts will lead to higher revenues and erase the deficits. This form of denial can take the form of dynamic scoring, supply-side economics and the Laffer curve (fondly embraced by Dave of First State Politics). The common thread of these beliefs, that tax cuts pay for themselves, has been refuted by the Congressional Budget Office in this report analyzing the effects of a 10 percent income tax cut:

The second form denial takes is to emulate Dick Cheney and simply state that deficits don't matter--end of discussion.

Robert Rubin, who knows a thing or two about global capital markets, clearly lays out the reasons why we should pay attention to the federal deficit:

Deficit spending is sending the national debt, as a percentage of GDP, back to the heights (or depths) of the Reagan/Bush era. And with no end in sight to deficit spending, the national debt will continue to grow.

Deficit spending is sending the national debt, as a percentage of GDP, back to the heights (or depths) of the Reagan/Bush era. And with no end in sight to deficit spending, the national debt will continue to grow.As I said, changing course requires an admission that there is a problem. Instead we hear various expressions of denial.

The first is to maintain the fiction that tax cuts will lead to higher revenues and erase the deficits. This form of denial can take the form of dynamic scoring, supply-side economics and the Laffer curve (fondly embraced by Dave of First State Politics). The common thread of these beliefs, that tax cuts pay for themselves, has been refuted by the Congressional Budget Office in this report analyzing the effects of a 10 percent income tax cut:

CBO finds that such a cut in taxes might increase output by amounts roughly in the range of zero to 1 percent on average over the first 10 years, among other economic effects. Under various assumptions, those macro-economic effects are estimated to offset between 1 percent and 22 percent of the revenue loss from the tax cut over the first five years and add as much as 5 percent to that loss or offset as much as 32 percent of it over the second five years.In other words, the best-case scenario is that a tax cut will result in a loss of 78 percent of revenue in the first five year and a loss of 68 percent of revenue in the second five years.

The second form denial takes is to emulate Dick Cheney and simply state that deficits don't matter--end of discussion.

Robert Rubin, who knows a thing or two about global capital markets, clearly lays out the reasons why we should pay attention to the federal deficit:

Virtually all mainstream economists agree that, over time, sustained deficits crowd out private investment, increase interest rates, and reduce productivity and economic growth. But, far more dangerously, if markets here and abroad begin to fear long-term fiscal disarray and our related trade imbalances, those markets could then demand sharply higher interest rates for providing long-term debt capital and could put abrupt and sharp downward pressure on the dollar.The good news is that we know that the federal deficit can be brought under control--because it was done not so very long ago. But "Rubinomics" has been a pejorative in the West Wing since the current regime took over.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home