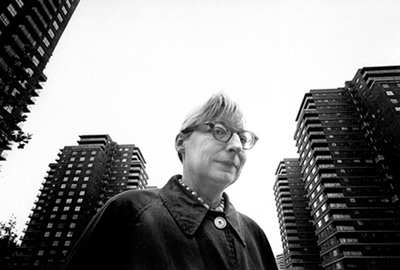

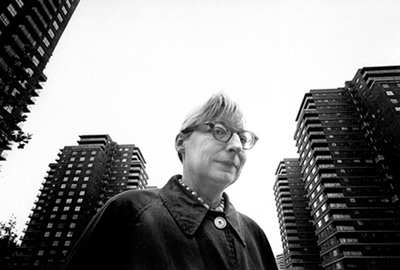

Jane Jacobs, 1916-2006

The world is full of would be iconoclasts who never had an original thought. Jane Jacobs produced more than her share of original thoughts by being an observer in a century of ideologues.

Jacobs lived in Greenwich Village in a particularly fertile time of American intellectual history, and helped to keep it from being paved over. In the 1960s, she successfully opposed a wrong-headed urban renewal plan for Greenwich Village and faced down uber-commissioner Robert Moses over a plan to put a highway through Soho in lower Manhattan. If Jacobs and her allies hadn’t opposed the powers that be, two of Manhattan’s most distinct neighborhoods would be very different today.

Jacobs lived in Greenwich Village in a particularly fertile time of American intellectual history, and helped to keep it from being paved over. In the 1960s, she successfully opposed a wrong-headed urban renewal plan for Greenwich Village and faced down uber-commissioner Robert Moses over a plan to put a highway through Soho in lower Manhattan. If Jacobs and her allies hadn’t opposed the powers that be, two of Manhattan’s most distinct neighborhoods would be very different today.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the practioners of urban renewal, in thrall of the bigger-is-better vision of a relentlessly efficient, antiseptic, urban utopia, seemed determined to extinguish the remaining signs of life from our urban communities. This futuristic vision, fed by architects fond of building big projects, and financed with the corporate capital and the public works budgets of the postwar era, destroyed countless city neighborhoods.

The philosopher Alfred North Whitehead wrote that Western philosophy is nothing more than “a series of footnotes to Plato.” It could be said that urban planning in our lifetime is nothing more than footnotes to Jane Jacobs. An exaggeration? Perhaps. But a book or article on urban planning that doesn’t take note of Jacob’s insights is inconceivable.

The philosopher Alfred North Whitehead wrote that Western philosophy is nothing more than “a series of footnotes to Plato.” It could be said that urban planning in our lifetime is nothing more than footnotes to Jane Jacobs. An exaggeration? Perhaps. But a book or article on urban planning that doesn’t take note of Jacob’s insights is inconceivable.

More importantly, the practice of urban planning has changed, and for the better, in the 45 years since the publication of The Death and Life of Great American Cities, written as a polemic from page one:

Death and Life presents other principles, like the value of mixed use and streetscapes that encourage interaction, that are now considered essential to creating and revitalizing neighborhoods.

Transportation planning has changed. ISTEA (The Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act), adopted in the early 1990s, made it federal policy that transportation spending had to be about more than building roads. ISTEA retooled the way communities across the country organize their transportation investment to include such blindingly obvious insights that walking around is as important a mode of transportation as driving around.

Zoning codes have changed. The City of Wilmington has, as part of its zoning code, a requirement that downtown buildings cannot present blank walls to the street. New Castle County’s Uniform Development Code is written to promote the virtues of community living, including basic items like sidewalks that allow residents to walk to the store around the corner.

Simple? Perhaps. But in the 1960s and 1970s, suburbs were designed in such ways that required a person to get in a car to that to travel short distances. The corner store? You couldn’t get there from here.

Jacobs gave us a fresh look at the economics of cities, again starting with observation. A review of the phone book can tell us a great deal about the sophistication of a city, again from Death and Life:

Jacobs wrote with similar originality about the links between ecology and economics (The Nature of Economies) and the decline of Western rationalism (Dark Age Ahead). Systems of Survival is a fascinating look at the differences between coercive institutions and cultures (governments and systems based on enforcing laws and regulations) and market-based institutions and cultures based on mutual trust.

Our cities are better places and our intellectual life is richer because Jane Jacobs had an instinct for keen observation and thinking clearly that led her to challenge many of the erroneous assumptions about cities and economics that infected 20th century thought.

Jacobs lived in Greenwich Village in a particularly fertile time of American intellectual history, and helped to keep it from being paved over. In the 1960s, she successfully opposed a wrong-headed urban renewal plan for Greenwich Village and faced down uber-commissioner Robert Moses over a plan to put a highway through Soho in lower Manhattan. If Jacobs and her allies hadn’t opposed the powers that be, two of Manhattan’s most distinct neighborhoods would be very different today.

Jacobs lived in Greenwich Village in a particularly fertile time of American intellectual history, and helped to keep it from being paved over. In the 1960s, she successfully opposed a wrong-headed urban renewal plan for Greenwich Village and faced down uber-commissioner Robert Moses over a plan to put a highway through Soho in lower Manhattan. If Jacobs and her allies hadn’t opposed the powers that be, two of Manhattan’s most distinct neighborhoods would be very different today.In the 1950s and 1960s, the practioners of urban renewal, in thrall of the bigger-is-better vision of a relentlessly efficient, antiseptic, urban utopia, seemed determined to extinguish the remaining signs of life from our urban communities. This futuristic vision, fed by architects fond of building big projects, and financed with the corporate capital and the public works budgets of the postwar era, destroyed countless city neighborhoods.

The philosopher Alfred North Whitehead wrote that Western philosophy is nothing more than “a series of footnotes to Plato.” It could be said that urban planning in our lifetime is nothing more than footnotes to Jane Jacobs. An exaggeration? Perhaps. But a book or article on urban planning that doesn’t take note of Jacob’s insights is inconceivable.

The philosopher Alfred North Whitehead wrote that Western philosophy is nothing more than “a series of footnotes to Plato.” It could be said that urban planning in our lifetime is nothing more than footnotes to Jane Jacobs. An exaggeration? Perhaps. But a book or article on urban planning that doesn’t take note of Jacob’s insights is inconceivable.More importantly, the practice of urban planning has changed, and for the better, in the 45 years since the publication of The Death and Life of Great American Cities, written as a polemic from page one:

This book is an attack on current city planning and rebuilding.The revolutionary impact of Death and Life comes from keen observation:

Think of a city and what comes to mind? Its streets. If a city’s streets look interesting, the city looks interesting; if they look dull, the city looks dull.Jane Jacobs started in motion the return to the architecture of community and a turning away from what became known as brutalism. HUD has been replacing unsuccessful high-rise housing projects with community friendly mixed developments. New urbanists are building urban and suburban communities that incorporate the virtues that Jane Jacobs extolled.

Death and Life presents other principles, like the value of mixed use and streetscapes that encourage interaction, that are now considered essential to creating and revitalizing neighborhoods.

Transportation planning has changed. ISTEA (The Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act), adopted in the early 1990s, made it federal policy that transportation spending had to be about more than building roads. ISTEA retooled the way communities across the country organize their transportation investment to include such blindingly obvious insights that walking around is as important a mode of transportation as driving around.

Zoning codes have changed. The City of Wilmington has, as part of its zoning code, a requirement that downtown buildings cannot present blank walls to the street. New Castle County’s Uniform Development Code is written to promote the virtues of community living, including basic items like sidewalks that allow residents to walk to the store around the corner.

Simple? Perhaps. But in the 1960s and 1970s, suburbs were designed in such ways that required a person to get in a car to that to travel short distances. The corner store? You couldn’t get there from here.

Jacobs gave us a fresh look at the economics of cities, again starting with observation. A review of the phone book can tell us a great deal about the sophistication of a city, again from Death and Life:

Classified telephone directories tell us the greatest single fact about cities: the immense numbers of parts that make up a city, and the immense diversity of those parts.For instance, Wilmington’s phone book features four listings under “Glassblowing” (at least one of which specializes in laboratory glassware) and two listings under “Automaton Consultants.” The phone books for larger cities will feature specialists not found in medium sized cities like Wilmington. Jacobs described how this came to be in The Economy of Cities. In Cities and the Wealth of Nations, she challenges the assumptions underlying the the many spectacular failures of economic development in the 20th century:

However, in the face of so many nasty surprises, arising in so many different circumstances and under so many differing regimes, we must be suspicious that some basic assumption or other is in error, most likely an assumption so much taken for granted that it escapes identification and skepticism.Instead of nations, Jacobs proposed that city regions are the fundamental units for meaningful macroeconomic analysis, an observation that hardly seems remarkable today.

Macro-economic theory does contain such an assumption. It is the idea that national economies are useful and salient entities for understanding how how economic life works and what its structure may be: that national economies and not some other entity provide the fundamental data for macro-economic analysis.

Jacobs wrote with similar originality about the links between ecology and economics (The Nature of Economies) and the decline of Western rationalism (Dark Age Ahead). Systems of Survival is a fascinating look at the differences between coercive institutions and cultures (governments and systems based on enforcing laws and regulations) and market-based institutions and cultures based on mutual trust.

Our cities are better places and our intellectual life is richer because Jane Jacobs had an instinct for keen observation and thinking clearly that led her to challenge many of the erroneous assumptions about cities and economics that infected 20th century thought.

Photo: New York Post

Update: Inga Saffron, whose terrific Skyline Online blog looks more than a little like this site, has an appreciation of Jane Jacobs that even uses the same photo. Inga writes:We are all Jacobsians now.

And those who aren't, should be.

1 Comments:

I didn't put two and two together when I first saw the title of your post, but then I saw the photo of "The Death and Life of Great American Cities" you posted. My land use controls professor highly recommended her book, which is on my post-bar exam list of books to read. Thanks for this great post.

Post a Comment

<< Home